The founder of futurism, the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, used language stripped to essentials. Insisting that 20th-century literature should express the characteristic dynamism of industry, he advocated a type of writing that would emulate the speed and tension of machines. He also became a leading proponent of Italian intervention in World War I (1914-1918) and was later an advocate of fascism.

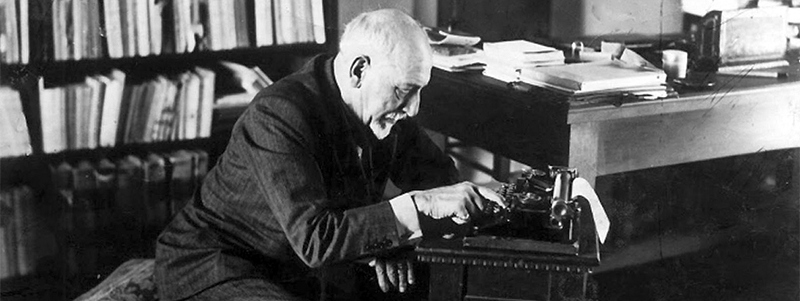

The most important thinker in early 20th-century Italy was the philosopher, statesman, literary critic, and historian Benedetto Croce, whose influence became worldwide. His bimonthly periodical La Critica (1903-1944) and his literary and philosophical works developed the ideas of the 18th-century philosopher Giambattista Vico and stressed the importance of intuition in art and of freedom in the development of civilization. His position of idealism was in strong opposition to the positivistic thinking then current in Italy. Croce believed that the intellectual should participate in public life and was himself openly opposed to fascism. His major philosophical work, Filosofia come scienza dello spirito (1902-1917; Philosophy of the Spirit, 1909-1921), consists of four volumes, one each devoted to aesthetics, logic, practical thinking, and history. His autobiography, published in 1918, is the record of a rich and varied life.

Besides La Critica, two other periodicals acted as the forum of different groups of Italian writers. Voce (1908-16), directed by the writer Giuseppe Prezzolini, helped to modernize Italian culture and introduce into Italy significant French, British, and American ideas. Outstanding among Prezzolini’s collaborators were the painter and writer Ardengo Soffici and the philosopher and writer Giovanni Papini. The other important periodical, Ronda (1919-1923), was reactionary in tendency and classical in inspiration. From its circle came the writers Antonio Baldini and Riccardo Bacchelli.

A unique figure throughout the first three decades of the century was the novelist, short-story writer, and playwright Luigi Pirandello, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1934. He introduced into his plays original dramatic devices that tended to bring actors and the audience into closer relation. Many of his plays are dramatizations of earlier stories, and most of them treat philosophical problems, such as relativism and multiple personality, with subtle psychological insight illuminated by graceful wit. The most famous of Pirandello’s plays include the following: Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore (1921; Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1922), Enrico IV (1922; Henry IV, 1922), and Come tu mi vuoi (1930; As You Desire Me, 1931). His novels include Il fu Mattia Pascal (1904; The Late Mattia Pascal, 1923) and I vecchi e i giovani (1913; The Old and the Young, 1928).

The emergence of fascism in Italy under Benito Mussolini endangered the vitality of Italian literature. Fascism failed to create a type of literature congenial to the government in power. The outstanding authors of the time reacted variously to the stifling intellectual conditions and to the contempt for human freedom contained in the Fascist political philosophy. Many were outspoken in their opposition, among them the writer and scholar Giuseppe Antonio Borgese. He realistically appraised the political situation in Goliath, The March of Fascism (1937), which was written in English, but which was not translated into Italian until ten years later. The novelist Ignazio Silone, who went into exile, became more famous abroad than in Italy for his searching political novels, notably Fontamara (1933; trans. 1934) and Pane e vino (1937; first published in English as Bread and Wine, 1936). Croce was forced into retirement under fascism; the journalist and diplomat Curzio Suckert, who wrote under the pseudonym Malaparte, served the government in an official capacity but ended by repudiating Mussolini. His most powerful work, Kaputt (1944; trans. 1946), depicts the moral and cultural degeneration of Europe under fascism.

After World War II a number of Italian writers came into international prominence.

Giuseppe Ungaretti, who ranks with Eugenio Montale among the foremost European poets of the 20th century, published his first book of verse, Il porto sepolto (The Buried Harbor), in 1916, marking the beginning of a period of great revival in Italian poetry. His works, the most important of which are Allegria di naufragi (Gaiety of the Outcasts, 1919), Sentimento del tempo (Feeling of Time, 1933), Il dolore (The Pain, 1947), and La terra promessa (The Promised Land, 1954), have been collected under the title Vita di un uomo (Life of a Man, 1958). His poetry is characterized by a sparing use of words and by his power to create illuminating images of unusual lyric intensity.

Montale’s major poems are found in three books: Ossi di seppia (1925; The Bones of Cuttlefish, 1983), Le occasioni (1939; The Occasions, 1987), and La bufera e altro (1956; The Storm and Other Poems, 1978); these were published in a collected edition, Poesie (1958; Poems, 1964). His lyric verse, often highly compressed and hermetic, contains a harsh and intellectual criticism of life and is at times deeply pessimistic in tone. In 1975 Montale was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature.

Poems by Salvatore Quasimodo reveal a passionate lyrical awareness of tragedy in modern life. Collections of these poems include Ed è subito sera (And Suddenly It Is Evening, 1942), Giorno dopo giorno (Day After Day, 1947), La vita non è sogno (Life Is Not a Dream, 1949), and Il falso e vero verde (The False and True Green, 1953). Quasimodo was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1959. The Selected Writings of Salvatore Quasimodo (1960) and To Give and to Have and Other Poems (1969) are English editions. His Complete Poems were published in English translation in 1983.

A few years after the war a new type of realism appeared in the Italian cinema, which enjoyed a period of unique creativity, and simultaneously critics began to speak of an Italian literary neorealism. Among the outstanding figures were Carlo Levi, who exposed the plight of farmers of southern Italy in his best-seller Cristo si è fermato a Eboli (1946; Christ Stopped at Eboli, 1947); Elio Vittorini, the author of Conversazione in Sicilia (1941; In Sicily, 1949); and Vasco Pratolini, who wrote Cronache di poveri amanti (1947; A Tale of Poor Lovers, 1949). Other major figures are Mario Soldati, noted for his Lettere da Capri (1954; Affair in Capri: The Capri Letters, 1957); Cesare Pavese, whose works include Tra donne sole (1949; Among Women Only, 1959), Il diavolo sulle colline (1949; The Devil in the Hills, 1959), and La luna e i falò (1950; The Moon and the Bonfires, 1950); and Vitaliano Brancati, a keen critic of contemporary Sicilian society as shown in Il bell’ Antonio (1949; Antonio the Great Lover, 1952). A novel that earned acclaim internationally, Il gattopardo (1958; The Leopard, 1960), by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, is set against the background of Sicilian life; it was made into an acclaimed film.

Besides Pirandello, the best-known Italian writer of the postwar period, especially in the United States, was Alberto Moravia, a prolific author notable for his novels and short stories of contemporary human situations. He wrote in a spare, realistic prose style about the moral dilemmas of men and women trapped in social and emotional circumstances. His most popular work is La ciociara (1957; Two Women, 1959), a novel about a mother and her daughter in war-torn Italy. The story was made into a successful motion picture. Another acclaimed motion picture was based on a haunting novel by Giorgio Bassani, Il Giardino dei Finzi-Contini (1962; The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, 1965). The story of the plight of an Italian Jewish family under fascism, it is set in the author’s native Ferrara.