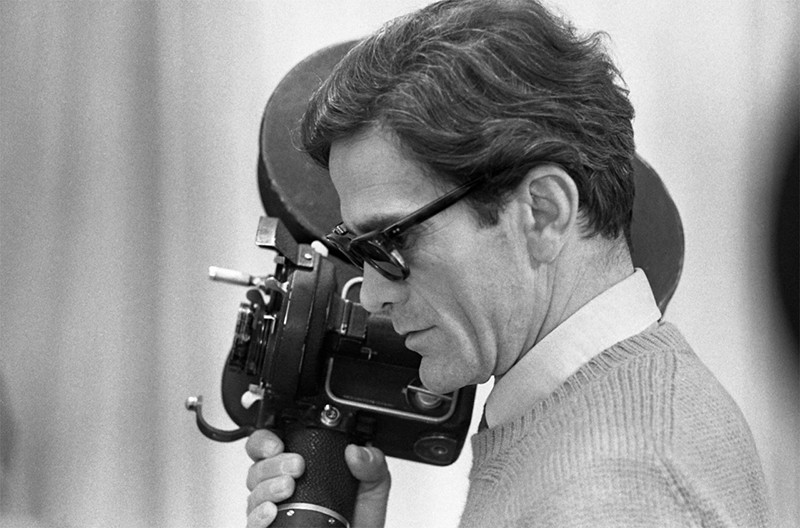

A groundbreaking force in Italian cinema and literature, Pier Paolo Pasolini stands out for his uncompromising critique of societal norms, a stance that continues to influence global art and politics. Known for his intense opposition to bourgeois values, consumerism, and societal conformism in post-war Italy, Pasolini’s career spanned literature, cinema, and journalism, challenging norms and advocating for the disenfranchised. His tragic death in 1975 left a lasting mark, cementing his status as a cultural and cinematic icon who continues to be studied for his political and artistic contributions.

Biography of Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pier Paolo Pasolini was born on March 5, 1922, in Bologna, Italy, a city known for its leftist political leanings. Pasolini showed an early interest in literature and poetry, writing his first poems by age seven. His family’s frequent relocations exposed him to diverse Italian regions, each influencing his cultural and political perspectives.

Pasolini’s youth was marked by intellectual curiosity and an affinity for literature, fueling his interest in writers like Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Shakespeare. He attended the University of Bologna, where he deepened his understanding of literature, philology, and aesthetics. By his twenties, Pasolini had emerged as a bold literary voice and was becoming politically active. In 1947, he publicly declared his alignment with Communism, hoping it could foster a new culture and alternative values.

Pasolini’s political views, combined with his openly queer identity, were highly controversial in conservative post-war Italy. Despite opposition, he continued to publish works that depicted the lives of the marginalized, such as Ragazzi di vita (1955), which presented the hardships faced by the Roman underclass. His first major cinematic project, Accattone (1961), brought his gritty storytelling to the screen and solidified his status as a revolutionary filmmaker unafraid of controversy.

Tragic Death and Unsolved Mysteries

Pasolini’s life ended abruptly on November 2, 1975, under mysterious circumstances. He was found brutally murdered near Ostia, a seaside district of Rome. Initially, 17-year-old Giuseppe Pelosi confessed to the crime but later retracted his statement, claiming that others were involved. Despite subsequent investigations, the case remains unsolved, with many believing that his political enemies played a role in his murder.

Literary and Cinematic Works of Pasolini

Early Writings and Poetry

Pasolini’s literary career began with poetry written in the Friulian dialect, where he expressed his appreciation for regional culture. His first novel, Ragazzi di vita, dealt with the lives of marginalized youths in Rome and attracted both acclaim and scandal. It marked Pasolini’s commitment to portraying the underrepresented and became a central theme across his body of work.

Debut as a Director: Accattone (1961)

Pasolini’s directorial debut, Accattone, portrayed the hardships of Roman street life. Despite—or perhaps because of—its raw depiction of poverty, the film was met with censorship, scandal, and critical acclaim. This set the tone for Pasolini’s filmography, which often highlighted the plight of society’s underbelly.

The Gospel According to Matthew (1964)

One of Pasolini’s most notable films, The Gospel According to Matthew (1964), reinterpreted the life of Jesus from a distinctly humanist perspective. Shot in black and white, it was acclaimed for its austerity and faithfulness to the Gospel, despite Pasolini’s known atheism. His portrayal of Jesus as a proletarian figure symbolized his empathy for the oppressed and remains a defining work in religious cinema.

Uccellacci e Uccellini (1966)

In Uccellacci e uccellini (The Hawks and the Sparrows), Pasolini combined comedy and mysticism in a film that explores philosophical questions with a humorous twist. Starring the renowned Italian comedian Totò, this movie showcased Pasolini’s range, allowing him to bring high art and folklore together in an accessible, imaginative way.

Teorema (1968)

With Teorema (Theorem), Pasolini pushed further into the provocative, examining the impact of a mysterious visitor on a bourgeois Italian family. Starring Terence Stamp, Teorema dismantled societal norms, reflecting Pasolini’s distaste for bourgeois values and his fascination with sexuality and existential upheaval.

The Trilogy of Life: The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, and Arabian Nights

Between 1971 and 1974, Pasolini directed a trio of films known as the Trilogy of Life: The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, and Arabian Nights. Drawing on classic works, these films are characterized by their celebration of sensuality, humor, and the earthy aspects of human experience. Pasolini saw these stories as embodying human freedom and natural innocence, presenting them in ways that delighted and shocked audiences alike.

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975)

Pasolini’s final film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, remains one of the most controversial films in cinema history. Based on the Marquis de Sade’s novel, it is a harrowing tale of oppression, depravity, and the abuse of power, set in the fascist-controlled Republic of Salò. With scenes of extreme violence and sadism, Salò serves as a condemnation of fascism, consumerism, and societal decay. Though banned in many countries, it is now recognized as a powerful critique of authoritarianism.

Pasolini’s Political Ideology and Social Critique

Pasolini was an outspoken critic of consumer culture, which he saw as a new form of repression. He believed that modern capitalist society was replacing genuine cultural expressions with homogenized, mass-produced culture. This view set him apart from leftist contemporaries, who celebrated the youth movements of the 1960s and ’70s. Pasolini argued that students and activists were unknowingly complicit in middle-class ideology, predicting that they would fail in achieving real change.

Despite his commitment to Marxism, Pasolini was critical of the Italian Communist Party’s (PCI) willingness to compromise with bourgeois values. His activism included articles in Il Corriere della Sera and collaborations with radical groups like Lotta Continua. His 1972 documentary, 12 dicembre, explored Italy’s “strategy of tension,” shedding light on government complicity in right-wing terrorist attacks.

Pier Paolo Pasolini Filmography

Here’s a closer look at Pasolini’s filmography, highlighting his major works and their thematic focus:

| Film | Year | Themes and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Accattone | 1961 | Poverty and marginalization in Rome’s underworld |

| Mamma Roma | 1962 | Urban poverty, starring Anna Magnani |

| The Gospel According to Matthew | 1964 | Humanist interpretation of Jesus’ life |

| Uccellacci e uccellini | 1966 | Existential themes, blend of comedy and mysticism |

| Oedipus Rex | 1967 | Psychoanalytic exploration of family and identity |

| Teorema | 1968 | Sexuality and bourgeois decay |

| Porcile | 1969 | Critique of fascism and consumerism |

| The Decameron | 1971 | Celebration of human sexuality and freedom |

| The Canterbury Tales | 1972 | Exploration of medieval life and sensuality |

| Arabian Nights | 1974 | Human experience through folklore |

| Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom | 1975 | Sadistic violence as a metaphor for fascism and power abuse |

Legacy and Influence of Pasolini

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s legacy endures, both in Italian culture and worldwide. His films continue to be analyzed for their innovative use of narrative, cinematography, and raw depictions of social and political issues. Pasolini’s critique of consumer society, his fearless depiction of sexuality, and his condemnation of fascism remain highly relevant today, and his work is regularly revisited by scholars, filmmakers, and activists.

His art represents a call to resist conformity, challenging audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about society and power. Though his life was cut short, Pasolini’s work continues to inspire new generations to question the status quo and embrace the power of art as a tool for social change.