The Renaissance in Italy was an extraordinary period of transformation, marked by flourishing economic, political, and cultural dynamism. As towns and cities transitioned from the feudal structures of the Middle Ages, they emerged as vibrant centers of commerce, industry, and intellectual exchange.

City leaders vied to expand their power through territorial conquest and by establishing spheres of influence, shaping the complex political landscape of the Italian city-states. Some, like Venice and Genoa, ascended to dominance, commanding Mediterranean empires and leaving a lasting legacy on trade and culture.

This era saw a remarkable revival of classical knowledge, spurred by the rediscovery of ancient manuscripts and the reevaluation of Greco-Roman literature and philosophy. These intellectual movements, which began in Italy, eventually spread throughout Europe, reshaping the cultural fabric of the continent.

The Rise of Humanism and the Rediscovery of the Classics

At the heart of the Renaissance was the intellectual movement known as humanism. Humanists were scholars dedicated to studying and reviving classical Greek and Latin texts, focusing on human-centric rather than divine ideals—a stark contrast to the medieval worldview dominated by theology. Their work represented a profound shift in intellectual priorities, emphasizing individual potential, worldly achievements, and critical thinking.

The humanists often found inspiration in the works of Plato, whose ideas contrasted with those of Aristotle, the medieval intellectual linchpin. This Platonic revival signified a fresh perspective, highlighting abstract ideals and the pursuit of universal truths.

Petrarch: The Father of Humanism

One of the most significant figures of the early Renaissance was Francesco Petrarca, or Petrarch (1304–1374). Known as the “Father of Humanism,” Petrarch bridged the medieval and modern worlds. His work marked the dawn of a new cultural era characterized by an intense focus on individuality and the revival of classical ideals.

Petrarch’s scholarship was instrumental in restoring classical Latin as a respected literary and scholarly language, countering the widespread use of medieval Latin. His efforts to refine Latin grammar, vocabulary, and style laid the groundwork for Renaissance humanism.

Petrarch’s Literary Contributions

- Prose Works: Petrarch’s philosophical writings, such as Vita Solitaria (1480; Solitary Life) and De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae (1468; Physicke Against Fortune), articulated a deeply introspective view of life and human nature, reflecting his individuality and modern sensibilities.

- Italian Poetry: His masterpiece, the Canzoniere (circa 1327), a collection of sonnets dedicated to Laura, introduced a new depth of emotion and personal introspection to European poetry. This work departed from the idealized approach of the dolce stil nuovo movement, instead offering raw, human sentiment.

Petrarch and Nationalism

Petrarch also displayed a nascent form of nationalism, envisioning Italy as the rightful heir to ancient Rome. In his Latin epic Africa, he glorified Rome’s civilizing mission, reflecting his hope for a unified Italy that could reclaim the grandeur of its classical past.

Giovanni Boccaccio: A Master Storyteller

Petrarch’s contemporary and close friend, Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), shared his admiration for antiquity while carving his own distinct literary path. The works of Boccaccio combined humanist ideals with a vivid narrative style, offering an unparalleled glimpse into the human experience.

Boccaccio’s Literary Legacy

- Narrative Prose: Boccaccio’s early romances, such as Il Filocolo (circa 1336) and L’Amorosa Fiammetta (circa 1343), revealed his talent for storytelling and character development.

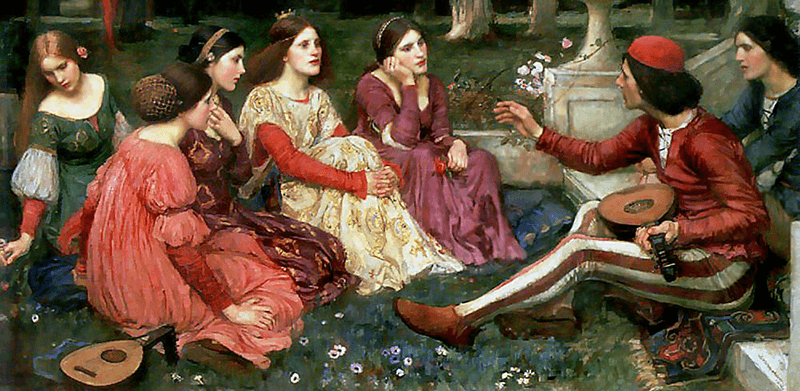

- The Decameron: His magnum opus, The Decameron (1353), is a collection of 100 tales told by a group of Florentines seeking refuge from the plague. This masterpiece celebrated human resilience, wit, and ingenuity, drawing inspiration directly from life rather than literary conventions.

Boccaccio’s influence transcended borders, inspiring writers like Geoffrey Chaucer, who adapted elements of The Decameron for The Canterbury Tales, and John Dryden, who used his works as the basis for his own poetry.

Advocacy for Dante

Unlike Petrarch, Boccaccio deeply revered Dante Alighieri. His final works included a biography of Dante and public lectures on The Divine Comedy, solidifying his legacy as both a writer and a preserver of Italy’s literary heritage.

The Tuscan Language and Literary Legacy

Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio were instrumental in establishing the Tuscan dialect as Italy’s literary standard. Spoken in Florence and surrounding cities, this dialect became the foundation of modern Italian. Their collective achievements fostered a sense of linguistic and cultural unity that resonated across Italy.

The Universal Renaissance Man

The Renaissance celebrated the ideal of the universal man—individuals excelling in multiple disciplines. Figures like Leon Battista Alberti, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo epitomized this ideal, contributing groundbreaking works in art, science, architecture, and literature.

Lorenzo de’ Medici: A Renaissance Prince

One of the most remarkable patrons of the period was Lorenzo de’ Medici, the de facto ruler of Florence. Known as “Lorenzo the Magnificent,” he was not only a skilled politician but also a poet and a passionate advocate for the arts. Under his patronage, Florence became a cultural powerhouse, attracting luminaries such as Michelangelo and Botticelli.

Angelo Poliziano and the Blossoming of Drama

Among the literary giants of the period was Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494), known for his refined poetry and dramatic works. His verse play Orfeo (circa 1480) is considered the first significant work of Italian drama, blending classical themes with Renaissance innovation.

Poliziano also made significant contributions to scholarship, producing critical editions of Greek texts and translating ancient works into Latin and Italian, furthering the humanist mission.

New Literary Themes: The Geste and the Pastoral

Renaissance literature embraced a diverse range of themes, from chivalric epics to idyllic pastoral tales:

- Chivalric Epics: Matteo Maria Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato (1487) revitalized the medieval geste tradition, laying the groundwork for later works like Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso.

- Pastoral Poetry: Jacopo Sannazzaro’s Arcadia (1504) achieved widespread acclaim, blending classical motifs with Renaissance sensibilities.

Tensions Between Pagan and Christian Ideals

As Renaissance writers celebrated worldly values, they often clashed with Christian orthodoxy. Humanists like Lorenzo Valla questioned papal authority, exposing dubious documents and challenging ecclesiastical traditions. Conversely, reformers like Girolamo Savonarola sought to curb the excesses of Renaissance culture, establishing a theocratic regime in Florence that ended in his execution.

Conclusion

The early Renaissance was a time of unparalleled cultural flourishing, where literature, art, and philosophy converged to reshape the intellectual landscape. Figures like Petrarch and Boccaccio laid the foundations for modern humanism, championing individuality, classical ideals, and a renewed focus on the human experience. Their works, along with those of countless others, forged a legacy that continues to inspire and resonate across centuries.